The first creatures with a backbone – jawless fish from hundreds of millions of years ago – did not. Scientists have been eager to learn how the evolution of the face unfolded.

A small, primitive armoured fish known as Romundina that swam the seas 415 million years ago and whose fossilised remains were unearthed in the Canadian Arctic is providing some revealing answers.

Evolution of the jaw

With Romundina at the centre of their work, Swedish and French researchers described in a study published in the journal Nature the step-by-step development of the face, as jawless vertebrates evolved into creatures with jaws.

The evolution of the jaw led to development of the face.

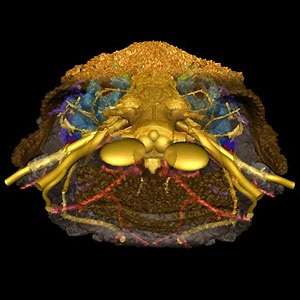

Read: Life on earth may have sparked into existence as early as 4.4 billion years agoThe researchers scanned the internal structures of Romundina's skull using high-energy X-rays at the European Synchrotron (ESRF) in France, then digitally reconstructed the anatomy in three dimensions.

Romundina, one of the earliest jawed fish, was found to boast a mix of primitive features seen in jawless fish and more modern ones that appear in fish with jaws. Its head had a distinctive anatomy, with a very short forebrain and an odd "upper lip" extending forward in front of the nose, they said.

Disappeared 360 million years ago

Romundina was a type of fish called a placoderm that thrived during the Silurian and Devonian periods in Earth's history but disappeared about 360 million years ago. It was small, but some placoderms like the fearsome Dunkleosteus became apex predators bigger than a great white shark.

Per Ahlberg, an expert in vertebrate evolution at Uppsala University in Sweden, said Romundina was roughly 8 inches (20 cm) long, had a small defensive spine on its back and had jaws without real teeth but with flat crushing plates.

Its front end was encased in armour, while its back end was flexible, with fins and a shark-like tail, Ahlberg said. It may have hunted small invertebrates like worms and crustaceans.

While the very first vertebrates were jawless, the only ones left are lampreys and hagfishes.

"The face is one of the most important and emotionally significant parts of our anatomy, so it is interesting to understand how it came into being," Ahlberg said by email.

Read: Do fish feel?

Image: These two images show the skull of the small fossil fish Romundina (415 million years old) scanned at the ESRF and digitally reconstructed in three dimensions. The internal structures of the face reveal the internal anatomy show a mixture of structures of jawless and jawed vertebrates (here in left lateral view, top). External bones of two different kinds in orange and pink grey, nerves and cranial cavity in yellow, arteries in red, veins in dark blue and inner ears in light blue; anterior part of the bone rendered semitransparent in bottom image (bottom). Credit: Vincent Dupret, Uppsala University

3-step transition

By comparing Romundina with other creatures, the researchers determined that the transition from jawless to jawed vertebrate with a face occurred in three major steps.

In the first step represented by Romundina, jaws evolved while a single nostril structure that reached under the brain in jawless vertebrates was replaced by a solid floor under the brain and separate left and right nostrils opening on the face.

The forebrain remained extremely short in Romundina with the nose located right between the eyes and the skull extended in front of it like a big bony "upper lip".

In the second step represented by more advanced armoured fish, the "upper lip" shrank to nothing, leaving the nose at the front of the face immediately above the upper jaw, but with the forebrain remaining short. In the final step as seen in modern jawed vertebrates, the forebrain and face lengthen.

"When you look at Romundina, it's like looking at yourself in the mirror, but with a 415 million-year-old image," Vincent Dupret of Uppsala, another of the researchers, said in a telephone interview. "It's like in a science-fiction movie. You look at the mirror, but it's not you. It's your ancestor."

The study was a collaboration among researchers at Uppsala, the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble. Read more at Phys.org

Read more:

A clever maths model sheds light on the origins of life

All about the evolutionary origins of human dietary patterns

Scientists discover how humans – and other mammals – have evolved to have intelligence

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners