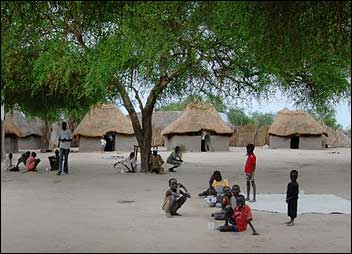

Women sit outside their ‘tukuls’ chatting and children jump rope and play. Yet one thing is different about this place: most of the people living here have tuberculosis (TB) and are staying here while they receive treatment.

Tuberculosis kills around 1.6 million people every year, almost all of them living in the developing world. For the most part, it’s a curable disease treated with a combination of antibiotic drugs developed over 40 years ago. However, the treatment is long, stretching over six months at least. Some patients might start to feel better after as little as two weeks on treatment, though they must be encouraged to complete the entire treatment course.

Treating TB in low-resource settings

In countries where TB is rife and free health facilities scarce, MSF has built special ‘TB villages’ where patients can stay for six to eight months and receive round the clock care, supplementary food, bed nets to protect them from malaria, blankets and clean drinking water. This setup greatly increases the chance that patients will finish their treatment course and be cured.

Medical coordinator Ronald Kremer explains: “TB drugs must be taken every day under the direct observation of health staff to ensure that patients complete their treatment. In rural southern Sudan, where patients often have to walk for hours or days just to get to a clinic, daily visits are simply not possible. So MSF had to come up with a different way of treating and caring for people with TB.”

This treatment method is used by MSF in a number of countries in the Horn of Africa, where nomadic populations are common or where conflict and insecurity have prevented medical centres and roads from being built. In Sudan, where over 90 000 new cases of the disease were diagnosed in 2006, MSF has been treating people using this ‘village approach’ for over ten years. In Lankien and Pieri, two of MSF’s projects in Jonglei State, the TB villages are attached to health care clinics. They are designed so that infectious patients live separately from other patients during the first stage of treatment, until they are no longer infectious and able to spread the disease. Women are allowed to bring their small children with them. If their parents are infectious, these children are given prophylaxis to prevent them from catching TB.

Taking care of basic necessities

As many as 122 people are currently being treated in Lankien and Pieri. Every morning patients line up to receive their drugs. As many of the patients are emaciated and very weak, MSF also provides patients and caretakers with supplementary food, including a weekly ration of sorghum, oil, salt and sugar. Each village has a cooking area and if there is no water pump nearby, MSF will install one in the village.

Although this treatment method has proven to be very effective, the frustrations and challenges that MSF faces in its TB programmes all around the world can also be felt here. After the first two-month ‘intensive phase’ of treatment, patients often feel a great deal better and men, in particular, want to leave the village to return to work. If people do stop taking their drugs, or default, before they finish their treatment, they will not be cured and there is a real risk that they could spread the disease to family or friends, or that they may develop a strain of TB that is resistant to the drugs.

Caretakers

In the TB villages every effort is made to ensure that patients do not default. All patients bring a family member or ‘caretaker’ with them to help look after them. “If a child or adult is sick and has TB, they need support,” explains Simon Mawich Gai, the supervisor for MSF’s TB village in Lankien. “Here someone from the family or community can come to take care of them and help them to cook and fetch water. When a patient is comfortable and has a caretaker with them they have fewer problems and are less likely to leave before they have finished their treatment.”

Yet, patients have to live away from the rest of their families for up to eight months and taking a number of drugs every day for such a long time is a huge burden. As Nyabang Biliw, whose 18-month-old daughter is being treated in Lankien, explains: “When my daughter’s cough didn’t go away I brought her to the MSF clinic. They did some tests and then explained to me that she had TB and that I would have to bring her here for treatment. It is hard living here, but I have no choice. When your child is sick you have to look after them rather than yourself. She has now improved a lot and has gained weight, but we must stay three more months until she finishes her treatment.”

Innovative and flexible approaches, like TB villages, have shown that it is possible to successfully treat TB in countries such as Sudan. However, what is really needed to tackle this global emergency are new diagnostic tools that are simple, reliable and adapted for use in remote, resource-poor settings; together with more potent drugs to shorten the length of treatment and to address drug-resistant TB. With these, thousands, rather than hundreds, of lives can be saved.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners