Summary

Atrial Fibrillation (AF) is a rhythm disturbance causing a totally irregular heartbeat. It most commonly occurs in the setting of existing heart disease, and can be a leading cause of stroke and sudden death. Many associated risk factors are known. AF may be intermittent or permanent. It is easily diagnosed, but the treatment may be tricky. Various methods can be used to re-establish a normal rhythm, and each of these has its own risks and side effects. Treatment may not be successful, and many patients progress to permanent AF, which needs managing. Successful prevention of AF rests in optimum managing of the associated risk factors.

Definition

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a rhythm disturbance in which the atria (receiving chambers of the heart) do not contract normally: instead of regular, forceful contractions which push the blood onwards into the ventricles (the pumping chambers), the atria just quiver in a totally disorganized way. The classical AF rhythm is described as “irregularly irregular” (This can be compared to the timing of a car being wrong. In AF then, even if the rest of the heart is working perfectly, its performance will be less than optimal, because the timing is out.)

In AF, blood flow through the atria is thus sluggish, and can result in the formation of clots within the heart: this is a high risk factor for pulmonary embolus and stroke. AF is thus important because of the increased risk of mortality. In addition, there is ineffective filling of the ventricles, leading to a reduced cardiac output.

AF may be:

- Paroxysmal – short lived and self-limiting, often less than 24 hours, and always less than 7 days. This may be recurrent.

- Persistent – lasts more than 7 days, does not self-terminate and may recur after treatment.

- Permanent – AF which has lasted more than 1 year, in which cardioversion has either failed or has nor been tried.

- Lone AF – this is AF of any type, without any heart or lung disease

What happens in the heart?

Normally, electrical impulses starting in the SinoAtrial node cause effective atrial contraction. This electrical signal then travels down, via the conducting system, to the ventricles, where it causes effective ventricular contraction.

In the state of AF, there is no organized electrical activity – only random, fast impulses. These are conducted to the ventricles, causing a rapid, but totally irregular heatbeat. If the majority of these rapid signals get through the conducting system, the ventricles may beat fast, but irregularly.

If the conducting system is abnormal/diseased, then most of these rapid signals are blocked, and the ventricles may assume a rate of their own, usually slow.

How common is it?

In general, the incidence of AF increases with age and underlying heart disease. In children, it only occurs associated with structural heart disease, and it is rare in healthy young adults. A large USA study of almost 1.9million patients found that men are affected more than women, and that the prevalence of AF is less than 0.1% in persons under 55 years, but >9% in those over 85 years. Similar findings came from a European study of 6808 patients

Causes and associated risk factors

Lone AF – these patients are usually male, under the age of 60, have no underlying heart disease, and often have a “trigger factor” bringing on the episode of AF. The most common trigger factors are:

- Sleeping

- Exercise

- Alcohol

- Eating

There is also a strong family history suggesting that the disorder/tendency may be inherited.

In most cases, however, AF is associated with an underlying heart problem, particularly those conditions leading to overfilling/stretching of the atria. The most common underlying conditions are:

Hypertensive heart disease

Poorly controlled hypertension increases the chance of developing AF almost 1.5 times, compared to a normal person. Whilst this may not be very high, the sheer number of persons with high blood pressure makes this a leading cause of AF.

Coronary artery disease

A patient whose CAD leads to a heart attack may develop AF if the heart attack leads to sudden heart failure.

Valve disease

Any valve disease which results in overfilling and subsequent stretching of the atria may lead to AF. The highest incidence of AF is found in disorders of the Mitral and Tricuspid valves : narrowing of these valves will cause blood to dam up in the atria, and leaking of these valves will permit blood to flow back into the atria. In both scenarios, then, the atria become overloaded and dilated, and this in turn may lead to AF.

Heart failure & hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

The incidence of AF in these categories may be as high as 30%.

Miscellaneous causes

- Pulmonary embolism, chronic obstructive lung disease (e.g. emphysema) obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, hyperthyroidism, can all lead to AF.

- Some medications used for these conditions, e.g. Theophylline, may have AF as a side effect in some persons.

- AF can also occur after surgery – cardiac or other surgery.

- Patients with other types of atrial rhythm disturbances can “degenerate” into AF.

- Dietary factors such as excess alcohol and caffeine are also implicated in AF

- Genetic – the exact inheritance pattern is not known, but AF may have a distinct familial tendency.

- Inflammation of the heart muscle may be associated with the production of antibodies which damage the heart

Congenital heart defects

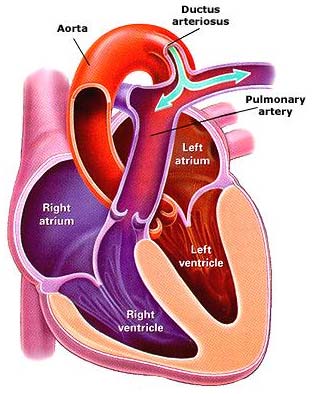

Up to 20% of adults with congenital defects may have AF : this is especially so with Atrial Septal defects, Patent Ductus Arteriosus and in other anomalies affecting the atria

Patent ductus arteriosus

Symptoms and signs

Because AF usually occurs against a background of existing heart disease, the symptoms may be overlooked or attributed to the existing problem.

However, in the absence of underlying heart disease, the irregular rhythm itself can cause

- Palpitations (the patient is aware of an unpleasant, usually fast and irregular) heartbeat

- Decreased exercise tolerance

- Shortness of breath

- Weakness and dizziness

- Sudden drop in blood pressure

- Angina

It is clear that any patient with existing heart problems who reports new symptoms, any of the above, must be investigated.

Diagnosis

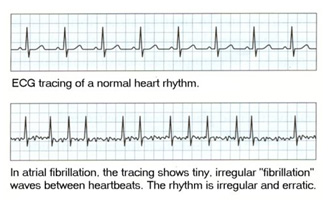

The mainstay of diagnosis is the Electrocardiogram (ECG) – this shows the pattern of electrical activity of the heart, and will reveal the rate, rhythm and any electrical conduction defects. It may also show signs of ischeamia, due to Coronary Artery Disease; of hypertrophy (increased muscle thickness) due to untreated hypertension; or valve problems.

Another useful investigation is the Echocardiogram: here sound waves are used to generate a computerized picture of the heart, its muscle and valves. The heart can be seen beating, the valve function can be seen, and the overall function of the hear can be assessed.

Due to sluggish blood flow in AF, there is a tendency for clots to form in a particular part of the atrium, called the atrial appendage. This part of the heart is not often clearly seen with a routine Echocardiogram, but a special Trans-Oesophageal Echocardiogram may be done to show this. It is important to know about clots inside the heart to minimize the risk of pulmonary embolus and stroke. (see Treatment)

A chest X-ray may reveal underlying lung disease as a contributory factor, and will confirm whether there is enlargement of the heart.

Blood tests may be done to check for thyroid function and anaemia.

For patients whose episodes of AF are intermittent, the ECG may be perfectly normal if done when the patient has not symptoms. For these cases, the cardiologist does Holter monitoring: this consists of fitting the patient with a mini-ECG which is worn for 24-48 hours while s/he goes about his/her normal life. Whenever they occur, any sudden episodes of AF are automatically recorded for diagnosis.

Treatment

Some important points to note:

- If an underlying precipitating cause is found, it must immediately be treated : this may stop the AF and allow normal sinus rhythm to re-emerge.

- In a nutshell, if the rhythm cannot safely be reverted to normal sinus rhythm and kept there, then the next best approach is to ensure adequate anticoagulation for stroke prevention, and control the rate at which the ventricles beat.

- The initial management of AF should always be done by a cardiologist, in a hospital setting.

There are three important issues to consider in AF:

- The rhythm

- The rate

- The possibility of clots

Rhythm control

In general terms, it is better to convert the rhythm back to normal Sinus Rhythm (SR). Before this can be attempted, it must be established whether or not there are clots in the heart. If clots are present, and the heart reverts to normal sinus rhythm, the organized, forceful contraction can dislodge part or all of the clot, which then travels in the blood stream. If the clot is in the Right atrium, the clot will travel to, and lodge in, the lung vessels. Small clots may do no serious long-term harm, but a large clot can obstruct a major lung vessel and cause sudden death. Clots in the left atrium are pumped out of the heart, and usually cause a stroke.

It is thus vital to know about clots in the heart before treatment is begun. If no clots are present, then an attempt can be made to restore normal rhythm. This can be done by means of medication or cardioversion (external shocking). The choice of method will depend on the clinical condition.

Cardioversion is usually delayed if the AF is of unknown duration (because clots may have formed by then) or if there is a known underlying condition which favours the formation of clots (e.g. certain valve disorders). In these cases, blood-thinning medication is used for up to 4 weeks, (or less if it can be shown that there are no clots in the heart) before cardioversion is attempted. Continued anticoagulation is advised for 4 weeks after cardioversion. Patients with sudden onset of AF are often unstable, and cardioversion may be used, especially if the AF has been of short duration.

Cardioversion may not be successful, or the patient may revert to AF after a few hours or days. In these cases, medication can be tried. There are many drugs which can be used, but the choice may be limited by e.g. the presence of heart failure. Some drugs can only be used for short periods, due to unacceptable side effects if used long-term. Because of these problems with medication, many cardiologists prefer to leave the AF alone, and merely control the heart rate instead.

Rate control

For patients who cannot be converted to – and kept in – normal sinus rhythm, an acceptable alternative is to merely control the heart rate at a speed best for the patient provided that adequate anti-coagulation is maintained. What this means is that the patient must be on Warfarin for as long at the AF persists. Whilst on Warfarin, regular blood tests must be done (at first daily, then weekly then monthly) to monitor the level of anticoagulation to keep it at the desired level. This test, the INR, is crucial in the prevention of strokes. The INR reading must be kept at a level which is enough to prevent clots and strokes, but not cause uncontrolled bleeding.

The issue of chronic af is now controversial, as certain operations have been devised to try to provide a permanent cure. Much work has been done in USA and Europe on this, but it requires highly specialized and costly equipment, and highly skilled operators, and there is not as yet conclusive evidence that it is effective enough to recommend it as a first choice. The procedure was originally devised as an open-heart operation, but endoscopic methods (with their own risk factors) are being tried, with some short-term success.

Outcome

Lone AF, that is AF in the absence of any underlying heart of lung disease, usually in patients <60years, has a very good outcome. Long-term aspirin therapy is recommended for these patients, with regular ECG monitoring.

It must be remembered that AF usually occurs in the setting of heart disease, especially heart failure. This makes it difficult to isolate the effects of treating the AF, because part of treating the AF is treating the underlying heart disease. The AF may disappear as the heart disease is treated, and it may be the improvement in the heart disease which leads to a better outcome. Statistically, AF itself cannot be proven to be a risk for mortality, but it is a strong marker for other factors which can affect survival.

The presence of AF is a risk factor for increased mortality in:

- Older persons

- Those with coexisting cardiovascular disease

- Women more than men

The morbidity and mortality is especially related to heart failure and stroke. It is therefore clear that managing AF is an important issue.

The overall outcome of rhythm control vs. rate control (see under Treatment) is similar, although the presence of normal sinus rhythm does reduce mortality. However, the adverse effects of some of the medications used to achieve this may offset their usefulness. This prompts many cardiologists to opt for rate control instead.

Recurrent episodes of AF may progress to permanent AF in about 19% of patients within three years of the onset of AF.

The use of Warfarin significantly reduces the incidence of embolus and stroke, though 1% of patients may experience some problems with excessive bleeding.

Prevention

Because AF is so strongly associated with underlying heart disease, good management of the known risk factors will help prevent AF developing, eg.:

- Hypertension – good control will prevent heart failure and AF

- Valve disease – optimal timing of surgery can prevent heart failure and AF

- Heart attack – good medical management, lifestyle changes and even well-timed by-pass surgery for patients with known coronary artery disease are advised

- Medications – avoiding medication known to have AF as a risk (eg stimulants)

Most of these preventative measures need to be initiated by a cardiologist who will probably already be seeing to the patient’s other problems.

Not much can be done in cases where the AF is associated with genetic factors, eg congenital heart disorders. Here too, the prevention/management will be in the hands of the cardiologist.

When to see your doctor

If you are not known to have any heart problems and suddenly experience any of the symptoms and signs listed above, please see your doctor urgently.

If you have been diagnosed with any of the associated risk factors, e.g. hypertension, and you experience ANY CHANGE IN SYMPTOMS, OR DEVELOP ANY NEW SYMPTOMS as listed, please consult your doctor.

Reviewed by Dr A G Hall, August 2007

For specific questions about atrial fibrillation, ask heartdoc on our forum.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners