This is an extract from “Apartheid and the Making of a Black Psychologist: A Memoir by N Chabani Manganyi”. Chapter 5 is an account of Manganyi’s early years as a forensic psychologist in apartheid’s courtrooms.

The first hint of a professional connection between psychology and the courts occurred unexpectedly after my return from the US in 1975. I had a consultation in Pretoria with David Soggot, a senior and well-known advocate. He and the instructing attorney were preparing for one of the historic political trials of the 1970s, that of members of the South African Students Organisation. The accused were imprisoned in what was then known as the Pretoria Central Prison.

In looking back I ask myself how I ended up working in the courts during such a turbulent period in South Africa’s history. Considering that little or no forensic psychology was taught either in South Africa or in the US, how did I approach my professional responsibilities in the courts at different stages of my development as an expert witness?

In retrospect I appreciate the fact that my initial approach to giving expert evidence was not only tentative theoretically, but also rather amateurish.

No established tradition

My starting point was that I could use my general knowledge of psychology, coupled with the clinical skills I had developed, to establish what had happened and why in each case.

However, what turned out to be of greatest assistance to me was the fact that not much was known, formally, about the subject by the primary players in the court scene (judges, prosecutors, counsel for the defence and instructing attorneys). There was no established tradition to speak of in our courts at that stage.

By the second half of the 1980s a small group of psychologists began to take on the role of expert witnesses. They started presenting evidence of extenuating circumstances in cases that often involved crowd violence in which innocent people had been killed.

When I first began working in the courts, I had sufficient reserves of courage and of clinically and academically derived professional self-confidence to venture into a new and unfamiliar professional terrain. Could it be that I sensed that all the major players were, in some respects, on unfamiliar ground?

Those psychologists who appeared as expert witnesses in the 1980s were not driven by a perverse recklessness. Some of us were members of an oppressed black majority faced with a remorseless political adversity that required a response from professionals and nonprofessionals alike. Our people’s freedoms and lives were at stake.

Although I was qualified and experienced as a clinical and academic psychologist, I had never set foot in a courtroom, least of all as an expert witness. That was until the trial of Anthony Tsotsobe, David Moisi and Johannes Shabangu, known as the Sasol Three, at the Palace of Justice in Pretoria in 1981.

The three men were part of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the military wing of the African National Congress. In the book “The Road to Democracy in South Africa” it is reported that Tsotsobe was part of the unit that carried out one of MK’s most daring operations, the attack on the Booysens police station in which an RPG-7 rocket launcher, also known as a “Bazooka”, was used for the first time on South African soil.

The accused were convicted of high treason and sentenced to death.

Working as a noviceMy first appearance in court was to present evidence of extenuating circumstances in respect of Tsotsobe. Although I cannot find the original text of my report, I remember the occasion vividly because the memory of Tsotsobe and his co-accused being herded down the stairs after sentencing is so unpleasant.

I was overwhelmed by the fear that I was seeing them alive for the last time.

Happily, the death sentences they received were commuted on June 6 1983. Tsotsobe was released from Robben Island in April 1991, but was gunned down outside his home in Soweto in September 2002.

Following that appearance in Pretoria a small group of human rights attorneys and advocates elsewhere in the country became aware of my availability as a possible professional resource. Consequently, throughout the 1980s my services as an expert witness were sought from as far afield as Pietersburg, Cape Town, Grahamstown and Durban.

My early experience included emergency calls for assistance from lawyers who sometimes contacted me only a day or so before the trial began. It put a great deal of pressure on me. I paid special attention to such matters as meticulous preparation of reports. That included conducting and recording pre-trial interview data and the structure of the written reports that formed the basis of my testimony.

One of the guiding ideas was that I would use all my clinical skills and knowledge to understand the events associated with the crime. In doing so I was also trying to find an answer to the question of why the crime had been committed in the first place.

In that way, some light could be shed on questions of intent, motivation and personal accountability. My main aim was to ensure that, in the end, a working psychological profile of the accused was developed and presented to the presiding judge.

Avoiding the death sentence

By the mid-1980s some South African courts had become combat zones in which the biggest prize for human rights activists and defence lawyers was to save the accused from being sentenced to death. It was some time before the full implications of expert evidence in mitigation and extenuation became clear to me. Once again I had to study my way out of ignorance in a focused manner.

Evidence in mitigation involves presenting evidence and arguments that will secure the fairest sentence for the crime in question. In some cases the search for such evidence led me to look for psycho-social deficits in the life histories of the accused. I took particular note of developmental deficits associated with poverty, family dysfunction, health and poor education.

The attraction of the psychological and social deficit model is that it is not difficult to present or for the judge to understand. The effective presentation of evidence is a formal exercise in storytelling and persuasion. It is expressed, if and when necessary, in the language of psychology and other people-based disciplines.

In recognising the value of psychological explanations and the formal exercise of well-reasoned arguments, it is important to acknowledge the role of interviews, life histories and, in appropriate instances, psychological tools (tests). It is also helpful to remember that, in practice, the terms “mitigation” and “extenuating circumstances” are like fraternal twins: close in meaning but not identical.

In practice, evidence in extenuation is closely associated with capital punishment. It is evidence outlining why a sentence other than the death sentence should be considered by the presiding judge.

Mitigation is less onerous in that the expectation is primarily a reduction in sentence following proper consideration of mitigating circumstances.

“Apartheid and the Making of a Black Psychologist: A Memoir by N Chabani Manganyi” is published by Wits University Press (2016).

Read more:

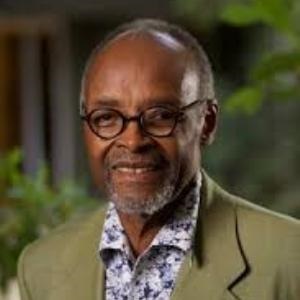

Chabani Manganyi, Emeritus Professor of Psychology, University of Pretoria

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners