While on a recent trip to the UK I had to travel over the Hammersmith bridge a couple of times a week. This bridge crossing the Thames in west London was designed by a man named Joseph Bazalgette, and like many examples of Victorian construction, it's not only practical, but also lovely to look at.

While this may only be of interest to bridge lovers, Bazalgette's other (and far greater) achievement is the reason that London never experienced another major cholera epidemic after the mid 1800's: a comprehensive new sewage system that changed both the health and landscape of that great city.

In the year 1832 a raging cholera outbreak left approximately 60 000 people dead, followed by additional epidemics in 1848, 1854 and 1867. Initially the movers and shakers of British health policy weren't too concerned as cholera was believed to be a 'disease of the poor' and, in Victorian times, being poor was considered an actual station in life.

Cholera jumps the class barrier

But when a cholera outbreak in Soho began to kill the not-so-poor, the disease suddenly gained status and became a national obsession. In the period between 1845 and 1856, more than 700 books on cholera were published in English, but the overall (and mistaken) opinion was that bad smells and vapours caused the disease.

A physician named John Snow disagreed with this belief and managed, through careful medical detecting, to show that tainted water sources played a vital role in the spread of cholera. But authorities rejected his theory and steadfastly maintained that it was all about the smell.

The stink that closed Parliament

For anyone visiting London today it's very hard to imagine the wide, strong-flowing Thames as it was in the summer of 1858. All the sewage and waste of a population numbering roughly 2 million people spilled into the river directly from the city drains or from urban tributaries and, in the heat and drought of that summer, it formed a slow-moving brown sludge that gave off a choking stench.

The smell of raw sewage and rotting waste grew so intense that Parliament had to close and for authorities, who had decided that cholera was a stink-borne disease, the time had come to do something.

Enter Joseph Bazalgette, civil engineer.

A massive undertaking

His proposal was to excavate and lay 1,800 km of glazed brick main sewers. These, in turn, would carry raw sewage away from every domestic outlet and dump it much further down the river Thames via two massive outfall pipes at Beckton. At this location the ocean tides would disperse it completely. In 1865 Edward (Prince of Wales) declared the system open, but it took ten more years to properly complete the system which is still in use today.

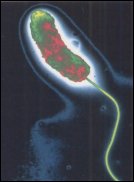

This was the end of the cholera epidemics. While the new sewage system had removed the stench that people mistakenly believed caused the illness, it also did the real job of providing clean water untainted with the water-borne bacteria Vibrio cholerae. John Snow's belief that cholera was microbial in origin was finally vindicated in 1885 when the bacillus was identified under a microscope by Robert Koch.

There were other happy by-products of Bazalgette's sewer project - like the Embankments built on both sides of the Thames using approximately 10 hectares of land reclaimed from the river by excavations. Part of the reclamation involved narrowing the Thames and building out on to the foreshore. A section of the tunnel for the Metropolitan District Railway was constructed and roofed over to provide a roadway which relieved city congestion. Above the tunnel, in addition to the roads, two public gardens were laid out.

Joseph Bazalgette went on to do what he seemed to like best: bridge design. Among others, he is responsible for such landmarks as Maidstone Bridge (1879), Battersea Bridge (1890), and the lovely Hammersmith Bridge (1887).

Driving over Hammersmith bridge, you can look into a Thames that now contains a few small varieties of fish (even trout), and is clean enough to swim in – if you fancy your chances against the river's powerful undertow. As rowers scull under the bridge, testing their mettle against the fast-flowing tidal pull, it's difficult to imagine that this was once a sluggish brown sludge that acted as the city's main sewer and water source.

Read more:

The discovery of Helicobacter Pyori

(Joanne Hart, Health24, January 2011)

Sources:

Images: Hammersmith Bridge, Arpingstone, Wikimedia Commons

The silent highwayman : Death rows on the Thames, Punch Magazine, Wikimedia Commons

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners