Brad has to do it. So does Angelina. Oh, and the Queen of course. Going to the toilet is humanity's great leveller and a necessary frequent reminder that we are all a lot lower than the angels.

The miracle of modern plumbing does allow us to keep some of the basics at a certain distance. Unlike the 1.1 billion people forced to squat on the ground because they have no access to any kind of toilets, let alone flushing ones, the rest of us can magically whisk the evidence away in a torrent of whitewater, Toilet Duck and pine air freshener, as if it had never been.

This is one of the primary reasons the Great Outdoors presents such a sharp and valuable learning curve to many.

Pooshrines, portaloos and other exit strategies

While hiking the Fish River Canyon, which boasts zero ablution facilities and requires carrying your life necessities on your back for five days, I met a young man with a toilet seat strapped to his person. He explained it was the only way his group had been able to persuade some of the “ladies” to come along, and gallantly offered my all-female hiking team the use of it too.

We were indignant. I for one am a veteran of the art of the carefully constructed “pooshrine”, something I'd had opportunity to perfect some years ago in the Andes when stricken with a spectacular case of Gringo Gallop. The shrine is a simple but substantial rock cairn, complete only when all signs of the deed are neatly hidden. It marks the spot in an unobtrusive yet unmistakeable manner and keeps everything in place, so to speak.

The other Ladies in my group seemed similarly conscientious, disappearing at intervals with matches to incinerate their used toilet paper.

There's nothing that detracts from the wilderness experience quite like a piece of soiled tissue waving at you from the corner of an otherwise pristine vista. But aesthetics aside, human waste can pollute water sources and pose health risks.

“Waste” here also includes litter, food waste and grey water (from washing), but it's the sewage element that's considered most problematic by both wilderness visitors and managers, such as those who considered it serious enough to organise an international conference on the issue called “Exit Strategies: Managing Human Waste in the Wilderness”.

As it turns out, shrines and pyres have their merits, but they are not exactly best practice models.

First, a note on a lesser evil

Relatively speaking, urination out of doors is OK. Urine from a healthy person is pretty sterile, and the risks it poses to health and the environment are minor. You still don't want to expose others to it unnecessarily, though, so choose a spot well off the main drag. Occasionally, urine atttacts wildlife which can damage plants and dig up soil, so rather pick a rock or gravel surface, and dilute the urine with a little water.

Faeces (let's just get over ourselves and use the word shall we?) pose problems of a quite different order of magnitude. Unlike urine, faecal matter contains harmful bacteria and pathogens, and these can remain viable for a long, long time in the environment.

Pack it in, Pack it out

Movements like “Leave no Trace” (LNT) espouse exactly that – what you pack / take in to the wilderness, whether toilet paper or food, you also pack / take out – regardless of the different form it may have acquired in the interim. If you are truly madly deeply Green, you will move through nature as lightly as a phantom. No one should be able to tell you were there.

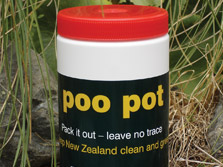

Packing out your intimate solid waste is not a lunatic green fringe idea; it's been familiar outdoor lore in several wilderness areas around the world for a few years now. In some national parks overseas, hikers and climbers are offered special “carry out” containers specially designed for this purpose, including such innovations as poo pots, poo tubes, clean mountain cans and WAG (waste alleviation and gelling) bags, which contain urine-activated powder to deodorise waste.

Poo Pot sold at Aoraki / Mt Cook National Park, New Zealand

Packing out is more crucial in some areas than others – deserts have very slow rates of decomposition, and narrow river valleys are easily contaminated, for example. In high alpine areas, climbers are being discouraged from tossing their waste into crevasses or placing it in “snow holes”, as this has made some of the more popular areas seriously distasteful (especially in summer when the snow melts), and the polluted snow has caused several gastrointestinal upsets.

Cat holes

If, like me, you still need time to get used to the idea of packing it all out, then Leave No Trace lets you off the hook somewhat with a second-best option wherever there's no designated facilty on the horizon: the “cat hole”.

This is not a perfect solution. Burying faeces may in fact slow down their decomposition; studies have found that in some areas, pathogens in buried faeces can still be viable two years later!

Smearing faecal matter thinly over a rocky surface in strong sunlight (a seriously considered and sometimes practised option in expert circles) is often a more effective means of disinfecting it. This is obviously Not Nice to perform, besides being highly anti-social unless you're somewhere so remote there's no chance of other humans coming across your experiment for months.

So the winner is the humble cat hole, which is pretty much as it

sounds, except on a larger scale for human needs. LNT recommends making

it 15-20cm deep and 10-15cm in diameter, so a small garden trowel is a

good implement to carry. Dig your cathole at least 60m (about 70 steps)

from water sources, paths and campsites, and it goes without saying that

it's best to choose a spot away from other cat holes. Several small cat

holes (the further apart the better) allow for faster decomposition

than one large pit latrine.

Sea to Summit's sturdy Pocket Trowel, designed for digging cat holes in hard ground. (It was previously named the IPOOd!, but Apple's lawyers failed to see any humour in this.)

Where possible, choose an elevated site in which water is unlikely to pool when it rains. The faeces will percolate down through the soil, but you want that process to be gradual so that maximum decomposition occurs before a water source like a river is reached. Avoid areas of likely heavy water flow, such as sandy washes, even in dry season.

Soil with high organic contact, which generally appears dark and loamy, is better for decomposition than sandy soil. Ideally you also want somewhere that the sun reaches, because heat and sunlight aids in breaking down and disinfecting waste. In desert or semi-desert areas like the Fish River or Richtersveld, the soil is low in organic content and decomposer micro-organisms. In such areas, make your cat hole shallower (10-15cm deep) to allow sun to penetrate.

You should also preferably convert the cat-hole into what the Backcountry Sanitation Manual calls a “mini-composting pile” with the following recipe: “break up the wastes with a stick, mixing them thoroughly with duff within the cat hole before covering with a mound of leaves and duff.” Duff is partly-decayed leaves and twigs, but failing that soil will have to do.

For the finishing touch, I think the Shrine can still play an important role. To my mind, this is one instance where you should leave a trace: a nice, naturalistic, but nonetheless unmistakeable cairn to show future cat-holers this is non-optimal digging area. In fact I'd be all for the development of an international cat hole symbol to mark such spots. It is uncanny how everyone tends to head for the same “discreet” spot, only to find it festooned with bits of toilet paper (or worse) from those who went before.

From the dustjacket of 'How to shit in the woods', the classic bestseller on the topic

Toilet paper and others

LNT would like us to pack out our used toilet paper of course, or use “natural” toilet paper, by which they mean handfuls of leaves and smooth stones and sticks and things. I'm not so sure about the wisdom of this, unless perhaps you're a trained botanist. What if the handful of leaves includes some blister bush? For example.

If you're not up to packing out the soiled paper (no, I'm not quite there yet either), then at least use a plain brand – unbleached if possible – and just a few squares. Burning it isn't a good idea if there's any vegetation about, because you risk starting a wildfire.

I'm afraid tampons and sanitary towels really should be packed in a plastic bag and packed out... Ladies. They don't decompose (or burn) easily and animals may dig them up.

Temporary pit latrines

Cat holes are generally a better option than digging one large hole for a communal latrine (perhaps adorned with a portable toilet seat), but the latter may be appropriate if, for example, you have a large group camping a few nights in one spot, or there are young children along.

Follow similar guidelines for choosing a cat hole location when you establish your latrine. Add a handful or two of soil (and duff, if available) each time the latrine is used to speed up decomposition and reduce odour.

The best sanitation tip of all

You know this one: wash your hands after going to the toilet and before touching food. For the outdoors, especially where water is scarce, I'd recommend a waterless hand sanitiser (e.g. Hand Sanz from Cape Union Mart) for use post- cat hole / poo pot.

This may seem a bit gross and burdensome at first, but it's yet another aspect of how we keep producing waste of all kinds, and assuming the environment will somehow handle the fall-out. And how we like to pretend we're somehow separate from nature, to the extent that we even deny a connection with our own bodily functions much of the time.

Making that species-saving paradigm shift towards a more mindful way of moving through the world may simply involve getting used to good new ideas and straightforwardly translating them into action.

As Miki Stuebe of the US National Parks Services Denver Service Center said pragmatically after the "Exit Strategies" conference: "It’s a matter of changing what is considered common practice, like the way disposing of one’s pet’s waste in city parks has become accepted practice".

- Olivia Rose-Innes, EnviroHealth Editor

References

Backcountry Sanitation Manual, Green Mountain Club and ATC, online edition.

Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics (2010) official website

Meyer, Kathleen. (2011) How to shit in the woods: an environmentally sound approach to a lost art.

UNICEF Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Annual Report 2011

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners