By Olivia Rose-Innes

Saving the planet lies in fostering the young's innate love and enthusiasm for life in all its multi-millionfold forms: the fuzzy panda cub, and the unphotogenic roundworm too.

On the airless tin-can flight to the 2010 Convention on Biodiversity Conference in Nagoya, Japan, I thought it would be a healthy mental diversion to list all the native Japanese species I knew:

Bamboo. Cedar tree. Crane. Plum blossom. Cherry blossom. Koi. Various other fish, for the sushi. Tiger (or is that China?)...Bamboo.........Hello Kitty! Tamagotchi! POKEMON: Pikachu, Bulbasaur, Poliwhirl, Wartortle, Squirtle, Geomander! – But let me stop there before I embarrass myself too badly.

Pikachu, a sort of electric mouse, superstar species of the Pokemon universe.

If you were even passingly acquainted with childhood in the mid-1990s, at least some of the names on my faltering species list will ring a bell: Tamagotchi, the Japanese digital pet (over 70 million units sold), and Pikachu et al from Pokemon, the sensationally successful game franchise, which held children in thrall worldwide; both are still hugely popular.

Tamagotchi, the world's favourite artificial pet

They also serve as allegories for the current mass extinction of life – a sickening 150-200 species lost per day – and the inadequacy of the man-made world to meaningfully replace it, try as we might with shiny simulacra.

The Pokemon story is particularly poignant in this respect.

Pokemon's developer, Satoshi Tajiri, an avid amateur naturalist and insect-collector as a child, watched his old bug hunting-ground shrink with each passing year:

The place where I grew up [Machida, a Tokyo suburb] was still rural back then. There were rice paddies, rivers, forests. It was full of nature. Then development started taking place, and as it grew, all the insects were driven away. I was really interested in collecting insects. Every year they would cut down trees and the population of insects would decrease. The change was so dramatic. A fishing pond would become an arcade centre.

The adult Tajiri re-created this lost world of creatures with his invented Pokemon, or “pocket monsters” – fantastical electronic “species” players collect and pit against each other. Pokemon evolve and have unique attributes and abilities that echo their real-world inspiration: of the guppy-like “Poliwhirl”, for example, Tajiri said, “There's little whirls on it because I remembered that when you pick up a tadpole, you can see its intestines because it's transparent.”

Tajiri's menagerie is addictive and fun, but these artificial animals are of course no more than grossly simplified, clumsy imitations of real beetles and frogs and turtles, or, to put them in their true light – breathtakingly intricate, interlinked organisms fine-tuned in form and function over millennia.

Yet many twenty-first century children have never encountered the originals. Urban kids in the United States can identify hundreds more product logos than they can their native fauna and flora. In a United Kingdom survey, 80% of youngsters couldn't tell the difference between a bee and a wasp; some couldn't distinguish these from a fly.

Kids obsessing over virtual diversions indoors instead of getting fresh air and muddy socks looking for creepy crawlies is more than just a pity. It means they might grow up without an innate sense of connectedness with other life forms and our sheer need for them, physical and spiritual – a concept biologist E.O. Wilson has famously promoted as “biophilia”.

Addressing audiences in Toronto, and Nagoya by teleconference, at the weekend, Wilson expressed the fear that children are not developing this deep bond with nature, and consequently, may not develop the drive necessary to fight to save it.

For save it we must. Life, Wilson reminded us, is the literal fabric of the world, as much as rocks and water are. If you were to remove all matter from Earth but left the nematodes -- the tiny, humble, but astoundingly ubiquitous roundworms that make up four-fifths of all animals on the planet -- you would still see its outline. The ground beneath our feet is not just a mass of mineral granules; a pinch of soil between thumb and forefinger contains, among multiple other life-forms, about a billion bacteria.

The great and terrifying difference between the inorganic and living earth, is that we are able to to halt and repair damage to the former, to some extent, but we have no way of conjuring up more than the ghosts of species lost. Living organisms aren't clockwork toys we can fix or replace when we break or mislay them; modern biotech, for all its brilliance, is nowhere near advanced enough. Conservation is a way of buying ourselves time while we continue to advance and figure out how better to survive.

Environmental education could be a potent tool to ensure we make it, say Wilson and other biodiversity champions.

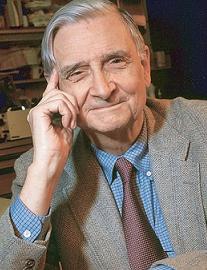

E.O.Wilson (photo: Jim Harrison)

Rekindling biophilia

How do we get a generation dazzled by the glow of screens to turn their gaze outside?

Wilson believes environmental education needs to be “infused” early to have a truly profound effect on young psyches – that it should have an honoured place right from the start, together with language acquisition and basic mathematics.

“Take kids out into nature,” he says, “but regularly, not just as some marginal, occasional activity when you set up the camping equipment in summer.”

Older children and teenagers can get involved in real, basic research through collecting and catalogueing. The living world is not the sole preserve of professional biologists. Wilson points out that of the sciences, astronomy and biology depend a great deal on “citizen scientists” to help keep watch over the skies and our vast, if dwindling fast, community of fellow life-forms. Even in the heart of the great cities that most of humanity now calls home, life persists and will reveal itself if we're actively looking for it.

“Go out, and explore,” says Wilson.

(- Olivia Rose-Innes, EnviroHealth Editor, Health24, October 2010.)

Photo: Craig Barker

References

Larimer, Tim. (1999). The Ultimate Game Freak. Time Asia.

Read more on biodiversity: Wonderful Life

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners